Addressing Homosexuality in Uganda (Pt. 1)

A first-hand report on how the issue of homosexuality is handled by Catholics in the country of Uganda.

This article was originally published by Crisis Magazine.

Last summer, when Fr. Alex Mugalaasi from Uganda invited me to visit to speak in five seminaries, each with 250 seminarians and about 20 priest faculty, I jumped at the proposal. And, oh, am I happy that I did! It was clearly an opportunity of a lifetime and a divine appointment.

The Church in Uganda is strong and needs to stay strong; it is under powerful attack from Western influence which wants it to ditch “traditional values” and embrace the LGBTQ+ agenda of the West.

I was hoping I could make a contribution by alerting them to the dangers they face from the West and also by deepening their understanding of these key matters—while urging that they develop a compassionate response to individuals who identify as LGBTQ+. Kevin Wells, a regular Crisis columnist, joined me to speak on “The Priests the Church Needs Now,” the title of one of his important and influential books. (Kevin, too, will be reporting on his trip to Uganda, which he extended with a trip to Tanzania.)

Fr. Alex is a friend of a friend: he has had a long-term relationship with a family in Omaha who years ago offered him accommodations and assistance when he came to the U.S. to study and ran into some difficulties. A most winsome person, Fr. Alex became so integrated into the family that he is considered a member of the family.

Spending three weeks with Fr. Alex, who is 38 years old and a deeply devout and faithful priest with phenomenal vision and energy who lives to serve, was possibly the highlight of a trip filled with highlights. It was also a true delight and a great help to have Kevin along; Kevin has a marvelously extroverted personality. He joined any group—priests, seminarians, guards, small children, store clerks, you name it—and engaged them in lively conversation. Both of us felt like rock stars—we were mobbed by children who had never seen white people up close—they expected chalk to rub off our skin! An excellent journalist and compiler of stories, in our many dinners with priests Kevin always had a worthy follow-up question that helped us understand better the Ugandan culture.

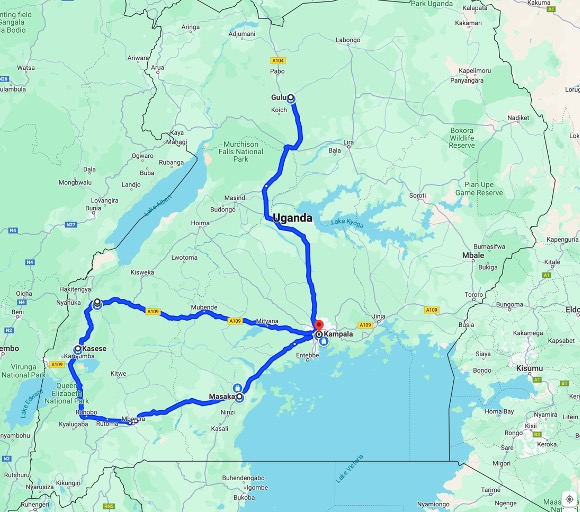

On days we weren’t giving talks, the three of us spent hours in a car as we traveled from seminary to seminary. Uganda is only as big as Oregon, but just getting through the capital city of Kampala could take hours: it has 7.3 million people and very few traffic lights (I saw four); I saw no stop signs, no yield signs, no traffic control of any kind (well, hundreds of speed bumps—ask my back!); and it has about one million “boda bodas” (motorcycles named from bicycles named for their usefulness in transporting drugs between the borders of Uganda to Kenya—hence, “border to border”) which operate as taxis. Boda bodas generally carry between three and five people and also carry cargo—sometimes five times the size of the boda boda (we saw one carrying a corpse!).

Riding through the city was one of the most harrowing experiences I have ever endured because the boda bodas weave in and out of the traffic as cars and trucks make three lanes out of two. It also filled me with admiration for the patience of Ugandans—I saw nary an altercation and never heard a honking horn.

Back to Fr. Alex and the purpose of my trip. Fr. Alex serves as the director of all spiritual direction for all the seminarians in Uganda. Because he has the respect of the bishops, he persuaded the committee on seminarian formation of the Episcopal Conference of Uganda to invite me to speak. We settled upon the topics of “Homosexuality” and “The State of the Church Today.”

Why these topics?

We decided on the topic of homosexuality not because homosexuality is a national problem in Uganda (though, as the Ugandans honestly acknowledge, no one knows—they don’t talk about sex) but because the West is zealously working to advance the acceptance of homosexuality in Uganda, and, indeed, all of Africa. I spoke only about male homosexuality since female homosexuality is much more complicated and it is male homosexuality that threatens seminaries. I also spoke about the various crises in the Church, including the dominance of the lavender mafia.

When researching homosexuality in Uganda, I internet searched “homosexuality Uganda”; I was led nearly exclusively to sites that reported on the work of NGOs who fight for LGBTQ+ “rights.” NGOs are non-government organizations who, without oversight of contributing countries, receive an enormous amount of funding from the United Nations. They are often, if not always, pernicious organizations that work to impose Western immorality on developing nations. (For an excellent exposé on the evil work of NGOs in Africa, see Obianuju Ekeocha’s book Target Africa: Ideological Neocolonialism in the Twenty-First Century.)

Because Uganda has strong laws against homosexual behavior, it presents a particular challenge to these NGOs. Reportedly because of the spread of HIV through homosexual activity, homosexual men found a reduction in willing partners and would prey upon minors, the disabled, and the elderly. To discourage predation on the vulnerable, such action is punishable by the death penalty. Those who are caught engaging in consensual homosexual acts or who promote homosexuality are subject to imprisonment for life.

It has been decades since any executions have been performed, but recently several men have been charged with capital offenses. Predictably, the U.S. is reconsidering aid and investments to Uganda, and the World Bank will no longer consider loan applications from Uganda because they object to Ugandan values. While even some of those who agree that homosexual acts are against God’s will may object to the harshness of the laws of Uganda, outsiders always need to try to understand the reasoning behind the laws and practices of other cultures. What is objectional is that we are ready to make Ugandans pay a great price if they continue to resist the infiltration of the gay agenda into their culture.

Those strong laws also presented a challenge to me because while I most certainly accept that homosexual acts are contrary to God’s will for sexuality, I have come to understand that those who experience same-sex attractions speak of these attractions as ones they did not choose, ones they find nearly impossibly difficult to control, and ones that they believe are virtually ineradicable, which makes chastity extremely difficult. This does not mean it is impossible for those who experience same-sex attraction to avoid the occasion of sin and to rely upon grace to help them, but chastity is a ferocious challenge for them.

In the U.S., my job is to explain and defend the Church’s teaching about homosexuality; even my Catholic audiences don’t understand why it is against natural law, or why the clear condemnations of homosexuality in Scripture still have force. I commended Americans for their sensitivity toward those who experience same-sex attraction but also have to caution that compassion should not bleed over into approval.

In Africa, it was not at all necessary to explain why homosexuality is wrong. It was necessary to explain the causes of homosexuality and to make a case for a compassionate response to those who experience same-sex attraction. These are matters that the Ugandans have not dealt with; in the U.S., we have had to, since the subject is thrust into our faces incessantly.

One fiftyish seminary rector, in his remarks after my talk, said that when he heard about homosexuality in his seminary studies, he thought, “that can’t really exist; what a waste of time to study it.” A few years later, when he went to Rome, he was asked for a blessing by a man who said he was a homosexual and didn’t want to be. That’s when he realized it exists and that it might not be a choice.

The first Ugandan priest I spoke with about homosexuality said he had no idea about sexual abuse as a possible cause of same-sex attractions, since Ugandans don’t discuss abuse or homosexuality. He said that pornography and fatherlessness are certainly problems but made no connection with homosexuality. It surprised me when he said poverty is a “cause” of homosexuality in Uganda and explained that homosexual predators, most of them allied with the LGBTQ-advocating NGOs, pay boys (or pay their school tuition) in exchange for sex and in exchange for the bought boys to introduce new boys to the predators. I heard this heartbreaking explanation several times.

You can imagine how they responded to pictures of our Assistant Secretary of State and a top energy official; of male homosexuals who have adopted children purchased and made through IVF; of males who present as females who compete in female sporting events—and invariably win; and of gay-pride parades. They were shocked that homosexual (and transgender) “rights” now override religious liberty. Since they watch Western media on occasion, it may not surprise you that they think most Americans are gay!

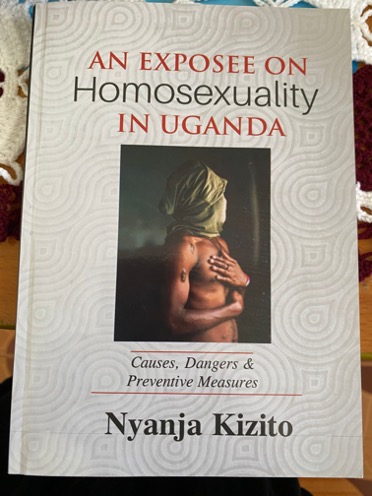

After one of my presentations, one young man gave me a book he wrote on homosexuality in Uganda (well, I guess some of them are on top of the topic!). The graphic blurb on the back shows that when Ugandans do talk about “delicate” matters, they mince no words!

In the next piece, I shall report on how I approached the topic of homosexuality in this context and how the seminarians and priest formators responded.

Support Ugandan Seminarians!

A new propaedeutic year is being established to provide better formation for Ugandan seminarians. Please click on this link to read about the program and how to donate if you are interested and able.

Leave a Reply