Catholicism in Uganda

Catholicism is everywhere in Uganda, but the Church faces challenges there as elsewhere.

This article was originally published in Crisis Magazine.

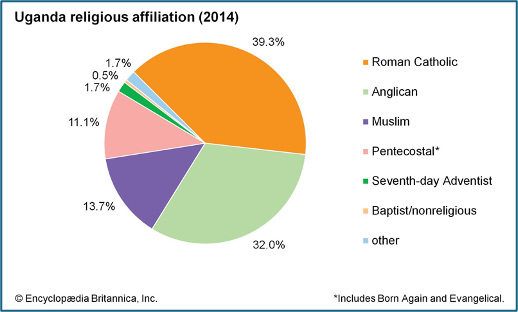

One reason I was so eager to visit Uganda was to witness its reputed vibrant Catholicism. Uganda is about the geographic size of Oregon (4.5 million population) and has a population of 45 million. Those I spoke with told me that 100 percent of Ugandans believe in God. Catholics are the majority at 39.3 percent and Anglicans account for 32 percent. Muslims have 13.77 percent and are investing a lot in Uganda; Pentecostals have 11.1 percent. Perhaps it was because of my Catholic bias, but I saw Catholicism everywhere—churches, schools, hospitals, and even stores and delivery vehicles with religious signage.

The first day, my host, Fr. Alex Mugalaasi, took me to a school that boards 300 boys who mobbed me like I was Taylor Swift. They wanted to touch someone who had white skin, and I wanted to rub their curly heads.

Father had offered to say a Mass for the teachers. We walked down a rough, clay path to a dismal looking compound where the teachers had their single-room residences. Plastic yard chairs were precariously perched on a cement stoop. The altar was a rickety table balanced on stones. To a person, all the teachers were dressed with real dignity in clean, pressed clothes that befitted their profession. One toddler was dressed in traditional African garb, another in a chiffon gown. Women sat in the front, men in the back. Everyone sang—all the verses of each hymn—with gusto and harmony.

To my great surprise and consternation, I was the only one who received Communion. It made me sad; I had heard so much about the vibrant faith of Africans and, at the first Mass I attended, no one received Communion.

So, what did Father do? He performed the role of a father: after Mass, he stepped forward and gently but firmly chastised them. He expressed his disappointment that no one had received; he said he knew that this was because they knew they were not worthy to receive—they were in a state of mortal sin, most likely because they were sharing a bed with their boyfriend or girlfriend.

He had used the wonderful analogy in his homily of everyone having within them a white dog that was good and a black dog that was bad. He said their choices were feeding the black dogs and starving the white dogs. He spoke of Lent as being a time where our fasting and sacrifices should feed the white dog and starve the black dog. I was sitting in the front and could only turn my head a little to see how the teachers were responding; but so far as I could see, they were all hanging their heads and avoiding eye contact with Father.

When Father was done, one of the male teachers came forward and gave a longish speech that pretty much repeated and expanded upon Father’s reprimand. He admitted that they had let their black dogs go wild and were not living as they ought. I couldn’t decipher his accent, so I don’t know how he managed to go on for 10 minutes or so, but he evidently got the message and concurred.

The whole event stunned me: that no Communion was received; that Father gave them a clear reprimand; and that the teachers evinced no hostility to what he was saying.

I came to learn that Fr. Alex’s behavior and the response of the teachers was not that uncommon in Uganda. They do live by the maxim “It takes a village to raise a child,” meaning they do not hesitate to correct those who are misbehaving, adults as well as children. And their respect for the Eucharist is real; at funerals when the priest might not know many of the guests, someone who knows the guests stands beside the priest and alerts him if anyone approaches to receive Communion who is in a state of serious sin.

(After Mass, I had an opportunity to chat with the teachers; I got the first of several inquiries about how a Ugandan can get a job in the U.S.!)

A very different experience was “Diocesan Day.” Once a year, parishes from each diocese gather at the cathedral for Mass and a full day of festivities. The cathedral and the setting were gorgeous and very festive: pavilions, sacred objects for sale, and lots of traditional food served after Mass. Parishes sent representatives and all the ladies from the same parish were dressed in identical colorful traditional dresses. People came very early to find seats and go to confession.

Any American who has been to a Mass in Africa marvels at the offertory procession that involves participants singing and swaying and carrying live chickens, large packages of toilet paper, cartons of eggs piled high, huge containers of cooking oil, massive bags of rice, cleaning supplies—anything that the bishop and those he serves might need.

Fr. Alex’s mother made a traditional dress for me so that I could be appropriately dressed for the occasion.

On Sunday, I went with Father to a school that houses 4,000 students, males and females, only some of them Catholic. One thousand attended the only Mass for the day—at 7 a.m.; they were not in the least bit rambunctious and appeared altogether attentive. One thousand young people shivering and bundled up in sweaters because it was about 67 degrees. A trained, lovely young woman directed the choir; virtually the whole congregation sang with gusto. It seemed most received Communion. Striking was the fact that the heads of both males and females were shaved—a wise practice, to be sure, but some of the girls complained about it to me.

Afterward, we went to a nearby Catholic church where about 200 younger children attended Mass. Among the hymns they sang was a classical arrangement possibly of a newly composed piece. It was sublime. Whereas the students were happy to sway and clap to modern hymns (which had its own kind of reverence), for this hymn they were still and seemed to experience the transcendence that such music facilitates.

Most of the chapels at the seminaries, as well as the cathedrals, were very traditional, and all had distinctive African elements, such as drum sets. There were some modern churches that were disappointing, but I won’t post images of those.

Nearly every church had renditions of the arrival of the White Fathers in Uganda—the same rendition, actually.

Bishop Francis, who was responsible for my getting permission to speak in the seminaries, invited us to dine with him and promised us he would make us genuine Italian spaghetti, which he did (delicious!). He had very modest accommodations but the most beautiful little, private chapel I saw in Uganda.

Early in the morning, we walked a short distance for Mass—to what seemed to me to be just a smallish village church, made like an outdoor pavilion. It was, in fact, the cathedral of the Diocese of Kasese, one of the poorer dioceses.

Bishop Francis was in the midst of building a new cathedral when an earthquake destroyed the hospital in the area. He invited the sickest patients to his “compound” and used the money he had collected to build a new cathedral to build a new hospital instead. He was dubious about when/if the government would use funds donated by international agencies for the purpose of rebuilding a much-needed building.

The rooms once used to house patients now serve as a nursery school for children nearby to provide for their safety. And the building of a new cathedral is still in abeyance. Seeing how modestly Bishop Francis lived and how he put the needs of his people first made me feel secure that any funds I raised for Ugandan seminarians would be put to good use.

At some of the talks, I asked if any of the seminarians or faculty had ever attended a Traditional Latin Mass (TLM). Not one answered in the affirmative and few seemed ever to have heard of it. But when I described it to one seminary rector, I barely made it through telling him about the “asperges” before he declared that he already wanted to experience it.

Before I went to Uganda, to my delight, I discovered there were a few places where the TLM was said, and I made an ardent request that we attend one. Fr. Alex readily granted my wish but did not initially warm to the idea of the TLM. He was favorable to the ad orientem position, the communion rail, and Communion on the tongue, but he just could not imagine the benefits of participating in a Mass said in an ancient language. I tried several ways to get him to grasp the idea of a sacred language, to no avail. I said he just needed to experience it.

The Latin Mass community in Kampala offers Mass at the very spot where Denis Ssebuggwawo, the second Ugandan martyr, was martyred. The parish is named after him and is administered by the Institute of the Good Shepherd out of France (though our celebrant was from England). It was impossible not to be acutely aware that this was the Mass that the Ugandan martyrs attended and to be extremely grateful for their witness. There were about 75 souls there; the singing was sublime.

Fr. Alex was won over immediately and agreed that all Ugandans should be exposed to such a beautiful liturgy (maybe it will be a requirement when I next go to Uganda!) and said he understood why it is good that there be a sacred language. He even asked if I thought the Church would ever return to this liturgy. It should not be surprising that Ugandans would respond favorably to the TLM. In spite of poverty, they are a dignified people with lovely manners who seem to have an authentic, natural reverence for the holy.

When my fellow speaker and travelling companion, Kevin Wells, asked Fr. Alex what was the biggest threat to the Church in Uganda, he responded “prosperity” and explained that when people believe they can rely on themselves, they stop relying on God. I certainly pray and hope the Ugandans will someday soon be able to enjoy a higher standard of living, which certainly seems possible given the abundant natural resources, the hard-working nature of the Ugandans, and their general affability. Again, one of my goals was to encourage the Ugandan seminarians to be wary of the false lure of the secular values of the West and to convince them that Africa must save the West, not that the West must save Africa.

I was privileged to be in Uganda right after Cardinal Fridolin Ambongo, President of the Symposium of Episcopal Conferences of Africa and Madagascar, had been to Rome to protest that Africans would not be blessing same-sex couples as mandated by Fiducia Supplicans. I told the seminarians that, so far as we knew, no other high-ranking prelate flew to Rome to challenge the Holy Father. Most of them were not familiar with the event, so I played it up as a dramatic moment of Africans coming to the defense of the Church.

As do many Americans and some top Church officials, I believe Africa may well be the best hope for restoring the Church to full fidelity. Cardinal Robert Sarah of Gabon (where Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, great defender of the TLM, served), recently remarked:

I have absolute confidence in the faith of the African people, and I am sure Africa will save the family. Africa saved the Holy Family (during the Flight to Egypt) and in these modern times Africa will also save the human family.

The image of Africa saving the Holy Family resonated beautifully with the Ugandans. Cardinal Gerhard Müller from Germany has expressed a similar view: Müller stressed that it is “a very important moment in [the] Church history that now the Africans are entering the place and taking over the leadershipin the Catholic Church, and it is a very good thing they are doing.”

One priest warned me that I had unrealistic expectations, and he may well be right. But at this point, I am not sure where else to place my trust, except, of course, in the Holy Spirit. Sights as the one below buoyed my spirit! That is Fr. Alex and one of his cousins.

In the next and final column, I will tell of some of the adventures we had while in Uganda, which sprinkled our already exceedingly interesting days.

Support Ugandan Seminarians!

A new propaedeutic year is being established to provide better formation for Ugandan seminarians. Please click on this link to read about the program and how to donate if you are interested and able.

Leave a Reply